Years ago, I remember my brother Ben describing the US Holocaust Memorial Museum as a place so haunting that you cannot possibly visit it and come away from the experience unchanged and unmoved.

It turns out that Ben was apparently into grand understatement that day.

The outside of the building is deliberately functional and eschews any pretense of the fancy styles common on the buildings lining the Mall. It honestly looks like something that would be more than happy to be emblazoned with a sign declaring it to be a prison of the worst sort.

And that’s when it struck me just how similar the building looks to the centre of the main building at USP Leavenworth (the “Big Top”) which we could see from our flat on the one hill in the entire state of Kansas when Dad was stationed at Ft Leavenworth.

If the building looks oppressive on the outside, that’s nothing compared to how oppressive the atrium feels when you pass through the security (which is pretty straightforward and not terribly intrusive).

You are meant to feel small and insignificant in the presence of an authority over you and that’s well before you get to wandering through the museum proper.

Let’s just say it is horrifyingly effective and the designers of this place knew what they were doing to get the maximum possible psychological effect upon the visitor.

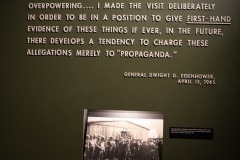

Now consider that you can choose to turn round and leave or not even enter the building at all. The people whose lives and deaths are documented by the exhibits didn’t have any choice in the matter of the horrors and evil they were subjected to during the Holocaust.

So if you’re already feeling oppressed and uncomfortable before you get to the exhibits themselves, one can only imagine the terror of people who were rounded up at gunpoint and sent to the camps and the realisation that they were very likely to die at any point of the journey.

The first step is to pick a identification booklet from a very large stack of them. Each booklet details the life of a victim of the Holocaust or at least as much as is known about them and you have no idea if your person survived the Holocaust or didn’t. You don’t *HAVE* to do select one but as the point of visiting is to fully appreciate the experience, there was no way I wasn’t going to take a pass on this important ritual.

I had a kind of weird feeling about the top card on the stack so I actually tried to get one from the middle of the pile of cards but it would not budge so I ended up taking the one that had given off a kind of weird vibe. When I opened it and saw the nationality of my victim, I noticed that he was Hungarian and we’ve gone straight from weird to flat out surreal. Imagine a Hungarian’s card being selected by another Hungarian born decades after he was in this place. Fortunately, the subject of the card I’d selected survived Bergen-Belsen and eventually immigrated to the United States in 1977.

One of the things that’s immediately apparent once you’ve selected your card is that the corridors are designed to give a feeling of claustrophobia and that’s before you even reach the exhibits themselves where there’s often a massive crowd of people.

I’ve never been a fan of being caught in a crowd. Whilst I’m not at all claustrophobic, being in close proximity to many people has never been something I’ve found comfortable. When my grandmother and I would head to downtown San Antonio for the street festivals during the three week fiesta period round the anniversary of the fall of the Alamo, I learned very quickly to tuck myself in right behind her as she would seemingly clear the crowds in front of her as if by magic. Eventually I’d see her weapon of choice that really made them move…an old-fashioned steel hat pin that she’d jab into whatever conveniently available bum was currently vexing her and they’d move very quickly and howling with pain but never being able to pin (!) the assault on her as we were already through the breach and she was looking for her next victim to have the temerity to stand in her way.

So it wasn’t just that the exhibits were disturbing and that there was a massive crowd at most of them but the realisation that as much as I was very much out of my comfort zone, what the victims experienced by being packed in close proximity like sardines and being terrorised in ways it is hard to imagine was far, far worse than what I was experiencing.

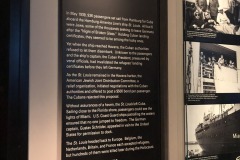

That’s when I arrived at the rail car that you cross through to continue through the museum and that feeling hit with a vengeance as I was assaulted with a sudden vision of hundreds of human beings packed in that rail car standing room only where they can’t breathe or move properly for hours as they were transported to some place that only God knew where they’d be by the time the train stopped.

I couldn’t get to the other side of that rail car quick enough and yet it still took what felt like an eternity to do so and another eternity to collect what wits I had left to me.

The museum designers had other plans for those wits because as you leave the rail car, you can’t help but notice a rather infamous iron sign with what appears to be an oddly-shaped “B” where the upper loop is grotesquely large compared to the lower one as it’s spelling out “ARBEIT MACHT FREI” meaning “work sets you free”.

That notorious sign means we’re about to arrive at the Auschwitz portion of the exhibit and there are no punches being pulled here. But as disturbing as this exhibit is, there’s a room that is just past the sign where you can listen to the voices of several survivors of Auschwitz giving a first person account of the horrors they witnessed and experienced in that most notorious of concentration camps. It’s one thing to see pictures and descriptions on the walls but it’s an order of magnitude more harrowing hearing the voices of people who *LIVED* in that wretched hell on Earth and were lucky enough to survive to tell of it.

The interesting thing is that none of the voices have a particularly angry tone to them. There are pauses where you know that the person is trying to fight through some particularly painful memories in order to share their experience in the hope that humans never do anything like that to other humans ever again but the most disturbing aspect of the recordings is that it’s delivered in such a matter-of-fact style that makes it all the more profoundly affecting.

I ended up listening for two loops of the soundtrack. The second time through was even worse than the first because now you know it’s coming and you can follow the narrative in the books that are laid out in this room that ironically is one of the least crowded rooms in the entire building.

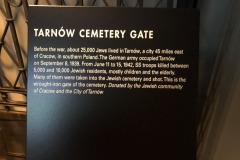

There’s a three storey tower exhibit of photographs of an entire village that was wiped out so completely that only the pictures remained. There are quite a few pictures in this tall tunnel, so many that you can’t really make out individuals on most of them. So many memories and lives extinguished from one shtetl (village) in Lithuania.

There’s a room that you pass through where there are glass barriers on both sides separating you from a sea of thousands upon thousands of shoes that were taken from the people before they were ushered into what they were told were showers. The sheer number of shoes and the realisation of how many times that didn’t make it to the exhibit. There are not words that can truly justify how profoundly haunting that room is…it just takes your breath away.

Interesting little factoid before we get to the finale…the bit of 15th Street SW that the museum stands upon was renamed in honour of Raoul Wallenberg, a Swedish diplomat assigned to Budapest who saved thousands of Jews by issuing them protective passports and other means to help them escape the Holocaust.

If you think the building is done with rocking your world, then you haven’t really been paying attention. Whoever designed this place knew what they were doing and there is no way in hell you can go through the entire experience and not be changed forever.

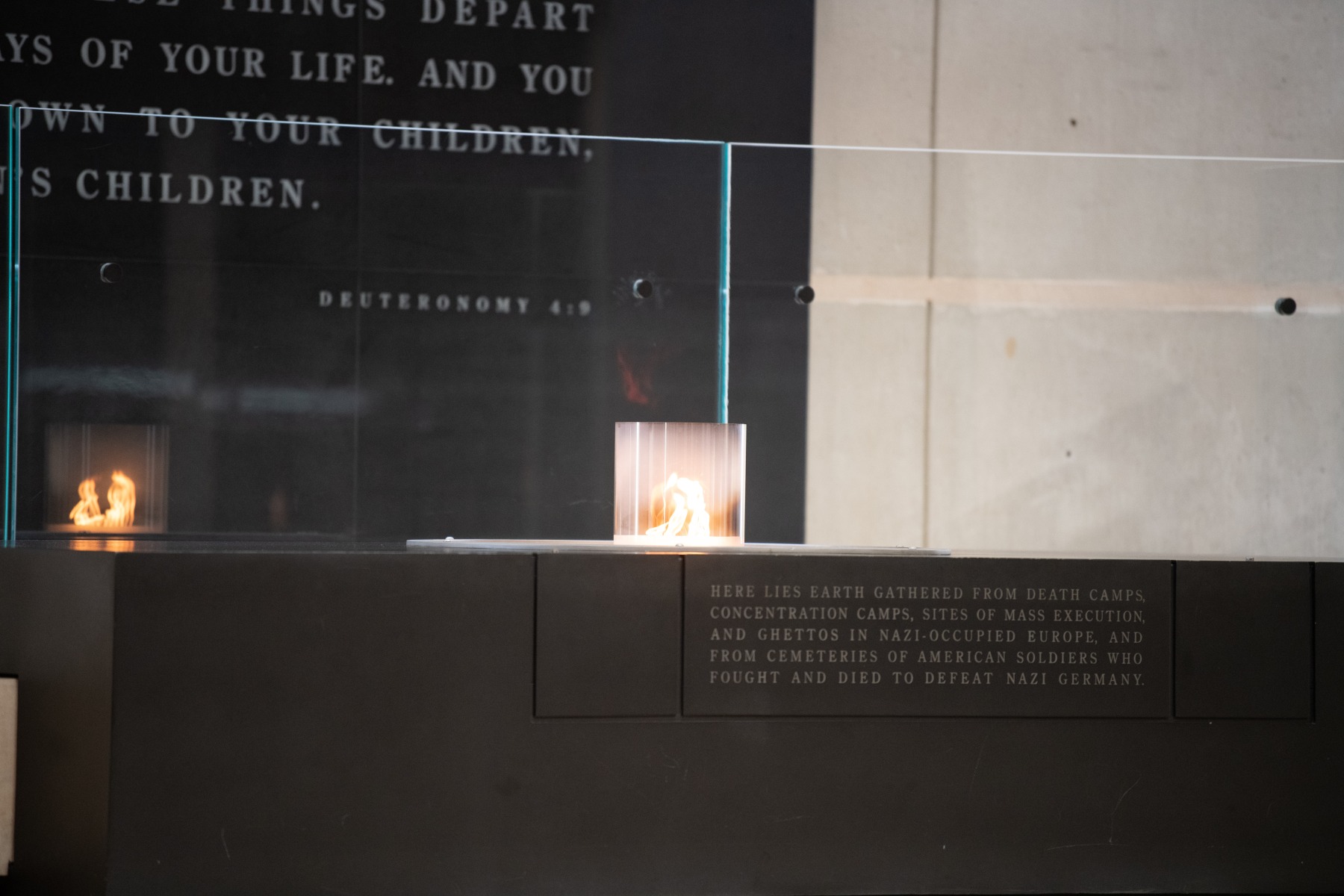

If you’ve stuck with the path through the museum to this point, the final place is the Hall of Remembrance.

But interestingly enough, you can smell gas fumes from the eternal flame in the room well before it actually comes into view which really adds to the crematorium vibe of the room. You will smell the gas down the long corridor to the Hall…you can’t help it.

The room itself is stark and barren with the flame at one side with the admonition from Deuteronomy 4:9 behind it exhorting one to remember what they have seen and pass it along to generations to come.

Surrounding the central open area are the names of the concentration camps on black walls and toward the ceiling more Bible verses stand watch over it all.

The flame draws your attention and in my case would not let me look away for many minutes. How many I couldn’t tell you but it was right up there with the time that I captured one of my favourite pictures from a trip to NYC of two NYPD cops looking at the names on the metal border round the footprint of the south tower and realising they were looking at the names of comrades that didn’t make it out of the building that day.

And yes, whilst staring at the flame to the point where everything else round me faded into the background…I’m not ashamed to admit that the tears flowed freely for those who endured such barbarism and cruelty and evil that the world had never seen before and a sincere hope that this world and our children will never see again.

I’m not ashamed to admit that at all.

As harrowing an experience as it was to visit the museum, I wouldn’t trade it for all of the money in the Two Worlds.

I’m glad I finally had an opportunity to do so and at last begin to try to understand far more than what I’d read in history books or seen in TV documentaries.

With anti-Semitism rearing it’s ugly head more and more these past few years, the mission of the museum of educating people in a brutal way what happens when we allow it to happen unchecked is even more critical now.

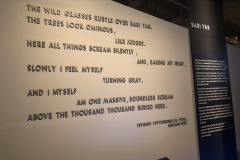

To do otherwise would be on the wrong side of the question that I saw on the side of the building before entering:

“Why didn’t more neighbours and friends help?”

We start by being willing to understand the totality of the evil and then vow to never allow it to happen again.

Not on our watch. Not ever again.

There’s a phrase in Magyar that you’ll often hear if you mention the Treaty of Trianon to a Hungarian:

Nem, nem, soha!

It literally means “no, no, never!”

We can never allow the Holocaust to ever happen again to anyone.

NEVER.