Last week, a Kenosha jury returned a verdict of “NOT GUILTY” on all charges in the case of Kyle Rittenhouse who was facing charges in the prisoner’s dock relating to his role in killing two men and wounding a third during the unrest that followed the shooting of Jacob Black by the Kenosha police.

My take on that particular case will be written presently but I want to concentrate on first exploring the notion of the jury in a deep dive with of goal of answering these questions:

- What is the brief history of the jury through the ages?

- How did the jury evolve in the United States?

- What are some of the pitfalls of the modern jury system?

- And most importantly, what can we do about making it fairer…if anything?

A Brief History of Juries

The notion of the trial by a jury of one’s peers goes all the way back to Ancient Greece where Athens had a mighty pool of 6,000 judges of which 500 would be chosen by lot and were overseen by a magistrate to decide disputes put before them.

In the case of serious disputes they might employ 1,000 or 1,500 of these judges to decide matters of fact and the law by majority vote which reflected the democratic nature of the Athenian society of the time.

This is a function that is split in modern courts where the jury decides the facts and truth of the evidence but the presiding judge determines the questions of law but in most other respects, these Athenian dikasts would be readily recognisable as jurors in modern society.

Ancient Rome decided that the huge pool of dikasts assigned to decide cases was a bit too unwieldy so often their courts would have a much smaller cohort of citizens known as the Comitia (judicial council) who would decide the cases put before them with a subset of members. Unlike the Greeks, magistrates (praetors) and other judicial officials not directly in the Comitia did not preside over the trial to ensure the suitability of evidence or witnesses. These functions would often be delegated to the Roman jury itself which would contain at least a couple of members who were learned in the law.

Whilst a lot of the practices of Roman law in Western Europe would largely go away after the fall of the Roman Empire and advent of the Dark Ages, some variation of the trial by jury would survive throughout the region in various forms, particularly amongst the Germanic tribes and the societies in Scandinavia.

Medieval Islamic society in Northern Africa and the Mediterranean all the way to Spain in the 8th-11th Century would be one of the first instances where the number of jurors chosen to serve on the lafif would be 12 which is the most popular size of modern jury. These jurors were selected from the community and had intimate knowledge of the players involved in the dispute and would render judgments of fact that were binding on the judge of the case.

Thus the notion of the jury would have likely have been introduced to England during the Anglo-Saxon migrations and was adopted and adapted later by the Normans who took over Anglo-Saxon institutions but would introduce the practice of using 12 members on a jury during the Norman Conquest owing to their experience with Sharia courts having conquered the Islamic caliphate in Sicily.

The use of a jury in court was firmly cemented in the English legal practice by the reign of King Henry II (who was largely credited with the innovation of the grand jury) and the forcing of King John to sign Magna Carta which guaranteed many rights including the right of trial by jury.

No free man shall be captured or imprisoned or disseised of his freehold or of his liberties, or of his free customs, or be outlawed or exiled or in any way destroyed, nor will we proceed against him by force or proceed against him by arms, but by the lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land.

Article 39, Magna Carta

These juries often conducted their own investigations into the cases brought before them rather than relying on testimony in court and the members of the jury were often quite familiar with the details of the case.

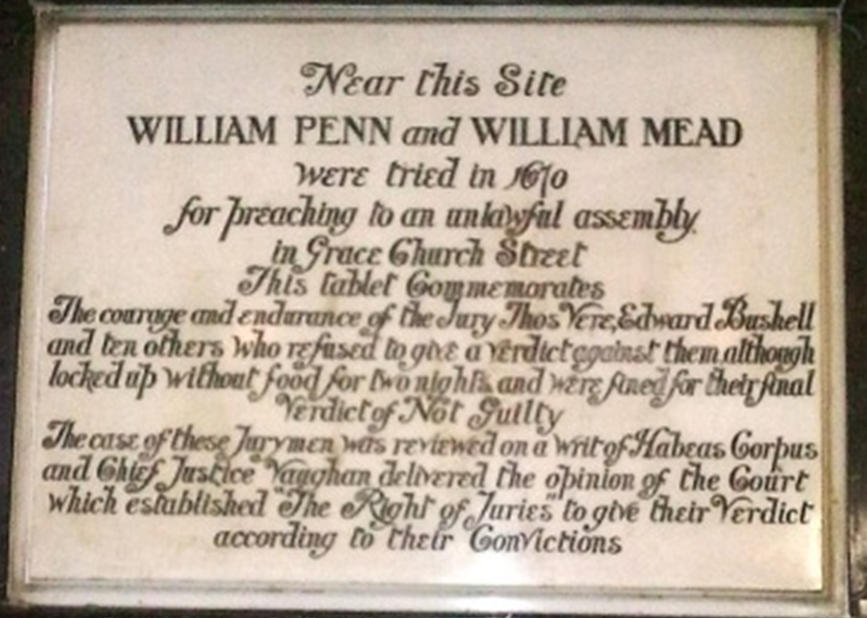

Even though the right to trial by jury was established in Magna Carta, it would take more than four centuries for the independence of the jury to render their verdict in a case would be finally be asserted as a matter of English law in 1670 during the trial of William Penn and William Mead who were accused of preaching illegally in defiance of the law.

The judge of the case refused to accept the jury’s verdict that whilst they were guilty of speaking in the church, they refused to convict the defendants of violating the Conventicles Act’s prohibition of speaking to an unlawful assembly (which as applied was any church other than the Church of England).

The jury was locked away in jail for two nights without food and still refused to return a guilty verdict whereupon they were found in contempt and jailed until the levied fine was paid. Ultimately, Edward Bushell’s jury would be exonerated and the right established for a jury to return a verdict without punishment though individual jurors could be held liable if they were guilty of misconduct whilst serving as a juror.

At this point, the jury in England looks and acts similarly to what we would expect of a modern jury and has since been adopted in many common law adversarial legal systems with most of these being descendants of the English Common law.

The Modern US Jury

“I consider trial by jury as the only anchor ever yet imagined by man, by which government can be held to the principles of its constitution.”

Thomas jefferson, 1788

After breaking away from the British Empire during the Revolution, many facets of the English common law were retained and the notion of trial by jury was enshrined in the United States Constitution and especially in multiple locations in the Bill of Rights.

In general, the jury is comprised of twelve jurors who are tasked to judge the facts of the case according to instructions on the specifics of the law provided by the court in a set of instructions. Jurors are required to only consider evidence before them that was lawfully admitted and presented in court with the instructions on the law in mind when rendering a verdict regardless of their feelings about or agreement with the law as instructed. Jurors are allowed to use their experience and common sense to come to their vote on a particular charge but are still expected to render judgment in an impartial fashion according to the law as it exists at the time of the incident.

Many jury trials will have several alternate jurors to hear the case simultaneously with the twelve that will ultimately be asked to return their verdict to allow for seamless replacement of jurors who are excused for misconduct or other reasons to avoid having to declare a mistrial and go through the whole expensive process again with a new jury.

The Trial of all Crimes, except in Cases of Impeachment, shall be by Jury; and such Trial shall be held in the State where the said Crimes shall have been committed; but when not committed within any State, the Trial shall be at such Place or Places as the Congress may by Law have directed.

US Constitution, article III Sec 2

Article III establishes the right of trial by jury for criminal offences which has largely remained intact though the Supreme Court established a threshold limiting this right to “serious” cases where the potential penalty is more than six months in jail (Baldwin v. New York, 399 U.S. 66 (1970)).

Cases involving lesser potential sentences may well find themselves in front of a jury but it’s up to the court hearing the case to allow a trial by jury or conduct a bench trial where the judge (or a panel of judges in some courts) hearing the case is essentially the jury.

Rights to trial by jury shows up in three amendments in the Bill of Rights starting with the accused’s favourite amendment of them all…the Fifth:

No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the Militia, when in actual service in time of War or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.

US Constitution, amendment 5

This amendment enshrines the right to indictment by the grand jury prior to answering charges of serious crimes in the prisoner’s dock in court. Unlike the petit jury that is the subject of most of this post, the grand jury conducts its examination of the evidence offered by the prosecution and/or police in secret and only if it agrees the evidence is sufficient for a trial for the criminal charges that were alleged will the case against the accused proceed with the handing down of an indictment.

The grand jury’s docket is often a relatively small one owing to the vast majority of alleged crimes being relatively minor where the defendant will often waive their right to the grand jury in the interest of speeding up the proceedings.

In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by law, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the Assistance of Counsel for his defence.

US Constitution, amendment 6

The Sixth Amendment guarantees the right to trial by jury in a criminal proceeding. As mentioned earlier, this right isn’t totally absolute and the jurisdiction is generally allowed to choose to conduct bench trials for lesser criminal offences that are often more pro forma cases with very little controversy at law.

It is not unheard of for defendants in these cases to demand a trial by jury anyway if they think their chances of acquittal are better than taking a chance on the judge assigned to their case, particularly when their defence is predicated on appealing to the emotions of the members of the jury.

In Suits at common law, where the value in controversy shall exceed twenty dollars, the right of trial by jury shall be preserved, and no fact tried by a jury, shall be otherwise re-examined in any Court of the United States, than according to the rules of the common law.

US Constitution, amendment 7

What is interesting about the Seventh amendment is that the right to trial by jury for civil cases only applies to Federal courts, and unlike the Sixth Amendment does not mandate that states recognise the right to trial by jury for civil matters (though almost all of them do via their own constitution).

The United States is relatively unique in that civil trial by jury has been abolished in pretty much every other jurisdiction and even here it is relatively rare accounting only for about 1% of civil cases. The vast majority of civil matters are settled well before the case is docketed and most of the rest are dealt with in small claims court which involves the litigants acting pro se in a bench trial in front of a judge.

Another distinction for civil trials by jury is that whilst they can empanel 12 members, they rarely do in practice and often these cases are heard by as few as 6 jurors.

Gaming the American Jury System

Section 2 of the preamble to the American Bar Association’s “Model Rules of Professional Conduct” lays out the expectations of lawyers towards the interests of their clients:

[2] As a representative of clients, a lawyer performs various functions. As advisor, a lawyer provides a client with an informed understanding of the client’s legal rights and obligations and explains their practical implications. As advocate, a lawyer zealously asserts the client’s position under the rules of the adversary system. As negotiator, a lawyer seeks a result advantageous to the client but consistent with requirements of honest dealings with others. As an evaluator, a lawyer acts by examining a client’s legal affairs and reporting about them to the client or to others.

American bar association “model rules of professional conduct”, Preamble

The zealous assertion of the client’s position and seeking a result advantageous to the client is at the heart of the actions taken at trial to empanel a jury that they feel will be most favourable to deciding the case in their client’s favour.

To that end, the system provides tools to both sides of the case to eliminate as many potentially hostile and/or prejudiced jurors as they possibly can.

Most jurisdictions draw their potential pool of jurors from the list of voters in the geographical area serviced by the court. The number of jurors the court feels the week’s docket requires (which may be dramatically less than are originally summoned by letter) are ordered to appear at the courthouse at which point they’ll be sworn to faithfully cooperate with the process of potentially being seated on a jury and given an overview of how jury duty works in that jurisdiction. Assuming the potential juror hasn’t found a way to be excused (either explicitly or by their juror number being so high that it’s outside the amount of jurors needed), then begins the wait for a trial.

The case being tried selects a subset of these potential jurors that are waiting for the call and subjects them to an interrogation known as voir dire (literally “to speak the truth” in French) which is intended to assess their suitability to serve on the jury and render an impartial verdict on behalf of the community.

Often, the first stage of voir dire is a questionnaire which the prospective juror will fill out with information potentially relevant to the outcome of the case which the lawyers on both sides will be looking for potential red flags. Most of the time these forms will ask if the juror is friends with or familiar with the parties in the case, have they already formed an opinion about the particulars of the case, have they heard about it or read about it on the news or social media, and so forth. Newer variations of the questionnaire will also ask for EMAIL addresses and social media accounts to aid the lawyers in doing their due diligence to weed out potential jurors who may have already formed and expressed an opinion on the case.

Sometimes these questionnaires can ask very personal questions of the juror that will make them feel very awkward or uncomfortable, particularly in sensational cases involving sexual misconduct or homicide but they are obliged to answer honestly having been sworn in earlier.

Should the prospective juror survive the questionnaire, then they’ve got to run the gauntlet between two different flavours of challenges that can get them tossed out of the jury box.

The first one is the “challenge for cause” which when used properly is intended to exclude jurors who have preconceived notions about the case or exhibit biases that would make them incapable of rendering a fair verdict in accordance with the law. Most of the jurors who would have been excused due to hardship or other reasons are long gone by this point but occasionally some slip through and this stage is usually where they’ll be challenged for cause.

The second type of challenge is the “peremptory challenge” which allows the lawyer to dismiss jurors without having to articulate why that juror should not be part of the ultimate panel.

Done properly with the correct intentions, these challenges of a juror’s suitability to serve can be an essential tool to try to ensure that the defendant has as fair a trial as is possible in an imperfect system.

However, these challenges can certainly be abused in ways that were not intended to try to seat a jury the lawyers will find more sympathetic to their case.

Often this sort of “jury gerrymandering” falls along racial/ethnic lines, particularly here in the South. One of the more disagreeable variations on this still persists many years after the “Jim Crow” laws were finally scrapped where black defendants will find themselves being judged by a lily white jury even though the community might well have a majority black population. Because African-Americans were often excluded from the vote, this provided a convenient mechanism to exclude them from juries in places where the pools are selected from the voter rolls.

Another variation on this could be seen in the jury selection in the recent case of the three white men accused of murdering Ahmaud Arbery (who was black) in Brunswick GA. Even though Glynn County’s population is roughly 27% African-American, only one of the twelve jurors who decided the case was black and the racial overtones of voir dire in this case were so pronounced that even the court was moved to comment that it had noticed the excessive use of peremtory challenges to disproportionately eliminate African-American jurors but that they felt that the trial should still proceed in spite of the evidence of jury whitewashing.

Gender can also play a role in jurors being challenged. In cases where the victim is a child, you can bet the prosecution is going to want to empanel as many women who have children of their own as they can whilst the defence will be doing everything in their power to see that those jurors don’t have a seat at the trial. Likewise in cases involving allegations where a woman was raped, the prosecutors will be looking to seat as many women (or men who have daughters) as they possibly can and the defence is going to do their level best to avoid as many of those jurors as well as retired law enforcement officers as they can.

Jury shopping can be a dangerous game that can get the lawyers in trouble with the court and potentially subject their case to a motion to dismiss or provide grounds for reversal upon appeal. In particular, using peremptory challenges to strike jurors based by race has actually been ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court starting with the Batson decision which alleged violations of the defendant’s Sixth and Fourteenth Amendment rights when the prosecutor in the case used peremptory challenges to dismiss all of the potential African-American jurors (Batson v. Kentucky 476 U.S. 79 (1986)). Batson has since been expanded in various jurisdictions to include other identifiable groups such as by gender or religious expression from being singled out by peremptory challenges.

Even when the lawyers seem to get the jury of their dreams, events can sometimes take a very unexpected turn when the case is handed over to the jury for a verdict.

Nowhere was this more evident than the original criminal trial of OJ Simpson in the matter of the murder of his ex-wife Nicole Brown and her friend Ron Goldman. The prosecution was aiming for female jurors who they felt would be sympathetic with the domestic abuse aspect of the case whereas the defence was looking to put as many black women as they could onto the jury based on research that they would much less receptive to the interracial aspects of the marriage. The resulting jury was ten women and two men with nine of the members being African-American, two white, and one Hispanic.

This jury was then sequestered (forced to live in a hotel with limited access to family and news media/papers/Internet) for a record 265 days during that marathon eight month trial.

When the jury finally received the case, it took only four hours of deliberation after enduring that mountain of evidence for months on end to acquit OJ Simpson of all charges which has been cited as the poster child of jury nullification where the jury returns a verdict that seems to be contrary to the law as instructed. Ultimately OJ Simpson would be found liable for their deaths and had a massive civil judgment entered against him but considering the penalties he was facing had he been found guilty in the criminal case, the jury’s verdict was found wanting amongst those who felt that the case against OJ had been proven.

How Can We Improve the Jury System?

(The following is my *OPINION* on how I think the jury system could be made fairer, your mileage may vary!)

The English who were learned in the law at the time of the Revolution would not necessarily recognise the modern American jury and would likely be bewildered at how it could possibly function effectively, especially the complete reversal of the notion of the jury members being experts on the participants and events being contested in court. English juries of the time certainly weren’t immune to external pressures being brought to bear upon them (particularly on behalf of the Crown) and their inherent biases affecting the verdict but ignorance of the case in the jury box was considered to be anathema to their practice at law.

However, “jurymandering” described above notwithstanding, the American legal system aspires to biasing the system to favour the rights of defendants and ensuring juries are not investigative bodies of citizens that are already intimately aware of the details is considered a feature of the system trying to ensure fairness rather than a defect.

Ideally, American juries would be composed of twelve reasonably intelligent laypeople who represent the community at large and who will diligently do their best to apply their reason and experience and the law to the evidence at hand and render a fair and impartial verdict on behalf of the community.

And even though there are plenty of examples one can point to where this doesn’t seem to be the case, I’d like to believe that by and large the system does tend to work as it was intended to provide a pool of citizens that are relatively unaware and uneducated about the case they are called to give a verdict.

The following are some suggestions (in no particular order) intended to make the jury selection process more fair and reasonable:

- Get rid of the “peremptory challenge” once and for all and force the lawyers on both sides to disclose a valid reason for dismissing a potential juror from service via the “challenge for cause”. Not only would this dramatically reduce the time and number of potential jurors required for voir dire to empanel a jury and alternates, it would also make detecting and enforcing Batson violations a trivial exercise. Arizona has become the first state in the US to do exactly that by statute which comes into effect in 2022.

- Challenges for cause should not necessarily be unlimited and courts should use their discretion to detect and sanction attempts to excessively challenge for cause. They can do this by restricting the size of the pool of available jurors which have been provided to the trial by the clerk of the court and asking for more should be a very rare exception reserved for the most notorious of cases in terms of media coverage for which a venue change motion might well be more appropriate.

- Jury composition should be reasonably representative of the ethnic mix of the community for whom they are rendering a judgment. This should be a no-brainer but as discussed above, stacking the jury by race for perceived advantage is something that is far too prevalent in modern criminal trials. Implementing this may be more than a little problematic…what demographic data do you use to establish the ratio, how often do you revise that data, how do you implement this without imposing quotas during voir dire, etc.? I won’t claim to have the answer to this but enforcing Batson more aggressively when it’s clearly being abused would probably go a long way to bringing the resulting jury mix much closer to the community at large. But the pool of jurors made available to the court should have a reasonable ethnic diversity of potential jurors as a good starting point. I’m not necessarily advocating something as restrictive as a fixed quota (Affirmative Action for JuriesTM?) but when a significant proportion of the community’s population is consistently underrepresented in jury boxes, it does need addressing to be more equitable.

- Sequestering a jury is increasingly rare given the advances in technology and availability of media but in the event it is needed to secure the jury against threats or harm, there should be a definite upper limit of the time they are sequestered. The fear that a potential juror could be essentially locked away for months at a time often dissuades potential jurors from making their best effort to serve. What was done to the jury in the OJ Simpson case should never happen again.

- The jury should have the right to privacy and anonymity as a matter of law and it should be a felony for anyone or any organisation to initiate contact with the juror during or after their service. Personally identifiable information about the jurors should be redacted from any official court documents and unofficial documents with that information should be effectively destroyed. I think the judge in the Rittenhouse case struck a nice balance between juror privacy and the news media insisting on the First Amendment right of freedom of the press where the jurors were provided with a packet of contact information for the interested media but were told they are under no obligation to speak to anyone and that should someone attempt to make unwelcome contact, the offender would be dealt with by the court as a matter of contempt.

So there you have it…my deep dive on the American jury: where it came from, how it works, and ideas on how to make them better and more equitable. Hopefully you enjoyed the ride and this document will be the background information when I mention noteworthy verdicts of interest (with the first one being a commentary on the Rittenhouse jury verdict coming soon!). 🙂